Within Labora’s creative collective, every member plays a part to make up the whole. And yet Labora’s true strength is built on the simple fact that each member – or part – is a whole unto themselves. Hannah Harkes is a perfect example.

If you were to meet Hannah working away at one of our presses as you tour Labora, you might assume from her impressive typesetting skills that she is a Master Printer. Well, she is. She graduated with honors in Fine Art Printmaking from Gray’s School of Art in her hometown of Aberdeen. And yet a Master Printer is not all she is.

Beyond Hannah’s mild-mannered and oft bespectacled exterior, you will discover a superb artist of impressive depth and range. So while she can produce prints with the amazing grace embodied in the true meaning of her name, Hannah is also an artist who works in more than just two dimensions – or even in the two+ dimensions which can result from deep or relief printing.

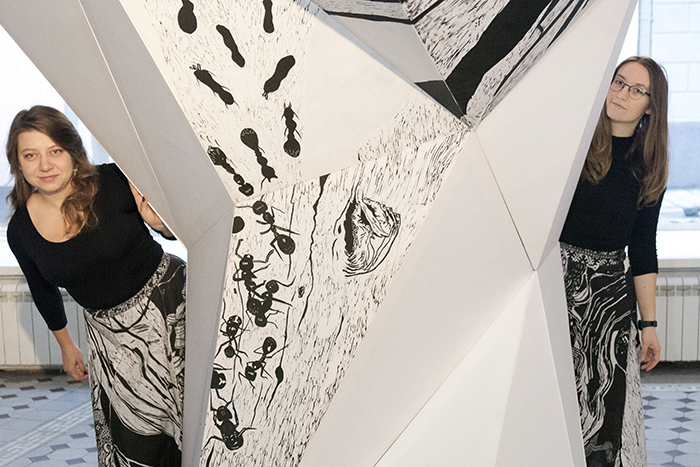

Indeed, Hannah will often create three dimensional objects like her soft-sculpture-costume Mutivana (2017) or transform her own 2D prints into 3D objects such as the tantalizing tree trunk of her most recent collaborative exhibit with Mari Prekup dubbed The Ground Beneath the Tree Moved Like a Congregation (2017).

Mari and Hannah at their exhibition The Ground Beneath the Tree Moved Like a Congregation – Photo: Mark Raidpere

Of course, there are also those moments when even three dimensions are not enough to contain her imagination – and so Hannah adds a fourth – time. As might be expected, some of her performance pieces are print-related such as her two beyond the box Graforotika pieces (2014-2015) with Mari Prekup. One involves Hannah and Mari climbing into a barrel to roll human-sized prints. For the other, Hannah dons a pair of red Soviet-made roller skates which double as ink rollers while Mari wears a matching pair to run their prints.

Given her love of printing and her talent for drawing, it should come as no surprise that Hannah will often choose comics – such as her multi-faceted Lollipop Elixir (2014) – as a medium for expression. And yet Hannah’s art is full of other surprises – especially when she follows her inspiration into other more unexpected media which are seldom seen as vehicles for art – such as games. Yes, Hannah can build a physical contraption like Hectare (2017) which – at least on its surface – resembles a traditional board game until you start digging a little deeper. But Hannah also loves to create other playful and interactive games from her Great War (2017) – a LARP or live action role playing game –to the multi-player/sleeper Chinese Dreams (2016) – or even the educational-developmental Guessing Game Jam (2014).

Graforotika performance by Hannah and Mari – Photo: Gudrun Heamägi

Hannah’s use of games is no accident. Her artful games are a way for her to interact with her audiences in new ways as she encourages others to participate. And in a country like Estonia known for its many introverts, Hannah’s art-games are a perfect way to break the ice and bring people together. Thanks to her gift for using art to engage with others and to deconstruct barriers, Hannah is a fully integrated member of Estonia’s art world as can be seen from her creative role at the Grafodroom Printmaking Studio or from her membership in both the Estonian Printmakers Association and the Estonian Artists Union. Impressive – especially when you take the time to admire her work as Labora’s Master Printer.

As your last name of Harkes serves a kind of cartographic indicator pointing back to a very specific historic farmstead in Scotland, how is it that you ended up working here in Estonia? And now that you’ve been based here since 2012, how do you maintain your connections back to Scotland?

As your last name of Harkes serves a kind of cartographic indicator pointing back to a very specific historic farmstead in Scotland, how is it that you ended up working here in Estonia? And now that you’ve been based here since 2012, how do you maintain your connections back to Scotland?

Of the name Harkes, my father told me as a child that the Harkeses have Viking roots. Whether or not there’s any truth in that, I treasured it growing up, for the idea of a connection to far-off lands in the North, across the sea, with a different language, different gods, and different ways of living. The Harkes family, from my grandfather’s generation and going back a few, were fisherman very much rooted in Aberdeen, a grey city I was always eager to leave.

It is only in the last few years that I’ve begun to call myself and think of myself as Scottish. My mother is English, and most school holidays were spent down south, visiting family and friends in Yorkshire villages and Lancashire towns, but the current political climate in the UK has left me reluctant to identify as British, so now Scottish it is, I suppose!

In 2011, the final year of my BA studies, I started looking for an artists’ residency to apply to, as I wanted to move straight on to the next project after graduating. I found the Polymer Culture Factory in Tallinn and came for two months, which became three months, which became six months as I moved into a nearby house in Pelgulinn, shared with other artists. For the next year, I moved between Estonia, Finland, and the UK, working on different exhibitions, but always coming back to Tallinn in between, as I slowly came to realise that I was becoming based in Tallinn.

I fly to Scotland around once a year because my father lives there. I feel an affinity with mountains and with rugged landscapes, I love the wind and I’m happy when it rains, but that’s about the extent of it – my home is in Estonia.

Speaking of geography, it seems that you like maps and that you like to use your imagination to create your own – especially ones that help map the imagination. How would you say that places and spaces feature in your work?

I’ve been on quite a few long-distance bike trips across Estonia and as a ritual, when I get home, I always trace the route on a map, using my memory and deduction to work out, a few days later, which small trails I took, where I doubled back, where I camped for the night, and so on. A map can contain so much more than geographical information and a line on a map is like a secret code containing memories, experiences and images.

When making a work, in almost all cases, the place in which it will happen, or be exhibited, is intrinsic to the development process, so whether I’m sketching the layout of a gallery space or reading about a town’s history whilst zooming in on Google maps, trying to get closer to a space or place feels like a vital process before presenting art there. The final work may or may not make any reference to a place directly – often not – but to imagine and plot the work in the place beforehand plays an important role in its emergence.

My latest exhibition, The Ground Beneath the Tree Moved Like a Congregation, with fellow printmaker Mari Prekup and architect Kaarel Künnap, was a collaborative exercise in mapping on different planes – physically mapping the Draakoni Gallery space and building a technically complex structure within it, as well as geographically mapping the phenomena of sacred groves in Estonia as we traveled across the country visiting these ancient sites. Simultaneously, this work mapped folklore and experience, taking two places, geographically distant from each other, and situating them side by side, for their shared narratives.

Over the last few years, you’ve taught printmaking and drawing, given talks as well as lectures, and have run workshops for both children and adults. As a teacher of art, how do you see your role – are you “paying forward,” are you passing on the art/craft, or are you trying to accomplish something else?

It all depends on the situation. Sometimes I am passing on technique, especially when teaching printmaking, as it’s very much a communal medium which thrives in shared workspaces and requires not only materials and facilities to be shared but also information and methods.

For the drawing and printmaking class I taught at EKA [the Estonian Academy of Arts], technical printmaking was taught alongside tools of collaboration – drawing exercises were done in pairs and groups to encourage interaction and shared ownership between the students.

For the drawing and printmaking class I taught at EKA [the Estonian Academy of Arts], technical printmaking was taught alongside tools of collaboration – drawing exercises were done in pairs and groups to encourage interaction and shared ownership between the students.

When I was artist in residence at the fine art school in Pietersaari, Finland, I adopted a role somewhere between student and teacher, inviting the students to collaborate with me and form an art school band. In this, I was introduced somewhat as an educator, but quickly stepped back and intentionally didn’t provide answers, so that the students would lead us by themselves.

During 2014, I co-directed Ptarmigan project space and some of the workshops I led there were themselves artistic experiments, or works. I saw the workshop format as an opportunity to experimentally construct a situation around a subject, an example of participatory art but one in which all participants were there willingly, having chosen to sign-up.

At Labora, I try to give children and adults an introduction to letterpress which highlights its historical significance whilst showing that there are so many possibilities to play with the process, especially when using contemporary materials and when approaching the tools as an explorer. I often learn a lot myself from the new minds I meet when teaching and from the new approaches students or workshop participants take. No matter the situation or the style of teaching, I hope most of all to inspire people to continue learning and experimenting, just as I remember well the classes, workshops, and people who have fired me.

Continue reading the interview with Hannah