EA Johnson is in town, meeting with Labora’s makers.

You can see what else he has been up to at flatfish.ee.

Enjoy his interview with Nestor Ljutjuk.

“Nestor! Open the floor!” – Нестор! Открой пол! And with these three magic words, I met Nestor. Of course, it took me a few disconcerting seconds to process what I’d heard as it isn’t every day that you hear the words “open the floor.”

At first,  I thought that I had misunderstood or misheard Nestor’s father Anatoli – or perhaps that my Russian-language comprehension had taken a sudden nose dive. But, lo and behold, the floor actually did open and then rolled up like giant wooden blind so that I was able to step down into the cave-like crypt under Tallinn’s Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Having heard the story of his namesake Nestor the Chronicler inside Kyiv’s Cave Monastery many years ago, the underground location of our first meeting seemed rather appropriate.

I thought that I had misunderstood or misheard Nestor’s father Anatoli – or perhaps that my Russian-language comprehension had taken a sudden nose dive. But, lo and behold, the floor actually did open and then rolled up like giant wooden blind so that I was able to step down into the cave-like crypt under Tallinn’s Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Having heard the story of his namesake Nestor the Chronicler inside Kyiv’s Cave Monastery many years ago, the underground location of our first meeting seemed rather appropriate.

Nestor Ljutjuk, however, is a very different kind of chronicler than that first Nestor because he uses images rather than words. And if its true what they say about just how many words a single picture is worth, then Nestor has been an incredibly prolific. When we first met back in 2002, Nestor had just been accepted to study graphic art at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Before he graduated in 2007, Nestor had already demonstrated his prolific talent and the breadth of his interests. He designed the first of several album covers for his various musician-friends. He illustrated a children’s book called Minu Jonn. And he painted icons for his church. Yes, Nestor graduated a year later than scheduled – but the reason for that was that he spent a year in Paris on an Erasmus Scholarship at the prestigious L’École Supérieure Estienne where he studied illustration, typography, and fine arts.

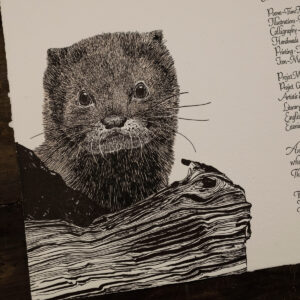

Nestor’s graduation coincided with his breakout appearance as the illustrator and designer of the original Poetics of Endangered Species: Estonia (2007). Nestor’s impressive, detailed drawings of Estonia’s rarest plants, animals, birds, and fish earned him positive reviews and a stand-alone exhibition at the Estonian Natural History Museum. Not content to rest on his laurels, Nestor went back to his alma mater to complete his Master’s in Graphic Art. That same year, Nestor worked as the designer and illustrator of the equally well received Poetics of Endangered Species: Ukraine (2008). Nestor’s artistic journey continued ever forwards as he mastered calligraphy and expanded his design portfolio to include not just books such as the Ark of Unique Cultures: The Hutsuls (2014) but also websites and certificates. And Nestor’s art could now be seen at numerous group exhibitions in Tallinn and Tartu (from 2008 onwards) as well as at his first personal exhibitions in Tallinn and Paris (from 2009 onwards).

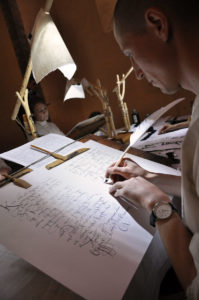

As far too many artists know, art alone seldom pays the bills no matter how talented you might be. And in a small world like Estonia, this is even more true. Fortunately, Nestor has found work in the field that he loves. In 2008, he started teaching master classes in printing, graphic art, calligraphy, and papermaking across Estonia – and he continues this process of “paying forward” by sharing his love for art with others. Impressed by his ability as a teacher, the Estonian Academy of Arts invited him back in 2009 to serve as a drawing instructor for their new students – and the invitations keep coming.

From 2009-2013, Nestor managed the day-to-day operations of the Ukrainian Cultural Center’s School of Calligraphy. And in 2010, he took charge of the Tallinn Paper Mill & Press which is now known as Labora. Nestor is not just Labora’s founder and managing director but also its resident illustrator and designer – plus he’s responsible for Labora’s artistic vision and direction.

You can see Labora’s impressive range of paper products both online and at its small shop in Tallinn on Vene 18. At either store, you can pick up a copy of Nestor’s most impressive accomplishment to date: his reimagined and redesigned Poetics of Endangered Species: Estonia (2018) with spectacular new illustrations. Not only will this book pull the floor out from under you, its unique blend of poetry, calligraphy, and art will set your imagination free.

What are your plans for putting your new illustrations from the reimagined Poetics of Endangered Species on display? Do you have any exhibits planned? And is it possible to get copies of the individual drawings like your wonderful image of the newt which some Hooandja supporters received?

While we recommend that everyone get the book, we’ve also printed six stand-alone illustrations from the Poetics in a larger A3 format suitable for framing. We plan to print an additional six images soon. And then we’re also preparing an entire series of new greeting cards based on drawings from the book – above and beyond the exclusive Black Stork card which Hooandja supporters received. All of these off-prints can be seen and purchased at our Labora Shop at 18 Vene Street and at our online store – or you can come directly to our workshops on 22 Laboratooriumi to get them.

We’ve also been fortunate in that on Wednesday 12 December, Tallinn’s House of Writers has agreed to help us present the Poetics of Endangered Species once again – an honor accorded to major publications. And I’ve also been talking to the National Library of Estonia about hosting an exhibit focused on the book and its illustrations.

Your impressive work on the Poetics of Endangered Species reveals an affinity for Estonia’s nature. How do you manage to keep connected with the natural world around you? And what did it mean for you to get a chance to redo your drawings of Estonia’s vanishing species?

It seems to me that most people who live in Estonia are connected in some way to nature. Estonia’s forests and sea side – plus its fens – are all places where people spend their holidays. While there is a certain kind of attraction to a busy city life, I spend every free moment that I can in the countryside recharging my batteries.

Of course, the place where I work every day – Labora – also happens to be a kind of a “secret garden” which has been visited by at least 28 different species of birds at our latest count. It is also home to a cat and a dog. You can find goldfish in our pond as well as stick bugs hiding amongst the plants. This is the first place in my life where I saw an owl. And it was here that I witnessed a falcon fighting a pigeon. My work environment is very important to me – and if I can make natural surroundings a part of that, then I’m truly happy.

Of course, the place where I work every day – Labora – also happens to be a kind of a “secret garden” which has been visited by at least 28 different species of birds at our latest count. It is also home to a cat and a dog. You can find goldfish in our pond as well as stick bugs hiding amongst the plants. This is the first place in my life where I saw an owl. And it was here that I witnessed a falcon fighting a pigeon. My work environment is very important to me – and if I can make natural surroundings a part of that, then I’m truly happy.

A lot of changes have taken place – both within me and around me – since I drew those first drawings for the original Poetics of Endangered Species ten years ago. Every illustration for the Poetics is something special. Even though Google allows you to explore a vast and wide-array of images from around the world, the real plants and real animals featured in our book still remain a bit of a mystery. Lots of my friends – as well as their friends – spend a fair amount of their time out in the wilderness. And while we know that there must be flying squirrels and elusive mink somewhere out there, I don’t know of anyone who has seen them in the wild. And, sadly, some animals have already vanished from our country forever.

Drawing animals that are in the process of disappearing provides me with a deep connection to the problems facing the natural world – as well as to other vital issues that we all face. It’s been a profoundly fascinating process.

As Labora’s managing director, what is your vision for Labora’s future? What new directions do you see the Labora collective exploring in the years to come?

I’m lucky to be surrounded by such a fantastic team. Sometimes I even find it hard to believe that such wonderful and capable people have gathered here at Labora. This year, we’ve had several great people join our collective. We have new individuals making paper, running our workshops, helping us with our calligraphy, and managing our shop. Sometimes I like to think of Labora as a ship – and every piece of paper, every work of calligraphy, every print, every workshop, everything that our shop sells or that our organization does becomes a kind of sail to help move us forward. Right now, it seems that every sailor on our ship is exactly the right person to keep our sails filled with wind so that our ship can sail onwards.

Over the coming years, we hope to focus on designing new paper products and print editions. In terms of papermaking, we want to take a new tack and focus on making paper for calligraphy. And this year we are developing a series of new workshops especially designed for young people. Fortunately, we can make use of our new facility – the Smithy – down the street at 25 Laboratooriumi. And, of course, we’re always open to new projects. In short, we think that we’ll have some new surprises up our sleeves for those who’ve been following what it is that we do.

Not only are you a multi-faceted artist who runs a small business, but you’re also a husband and a father of three children. Tell us a little about them – and about how you manage to balance all the different and equally important demands on your time.

I’ve been blessed with a wonderful wife and three great kids. Each one of us is very different and yet we’re all just a part of one family. Sometimes it seems that we’re different for a reason – to help each other polish our individual rough edges. Everyone in our family has something to learn from each other. This makes our family life both very exciting and quite complicated at the same time.

Mara and I believe in early education. Although it sometimes seems that children will remain small for such a long time, this stage will pass surprisingly quickly. And so, I understand that every moment that I can spend with my children is more precious than gold. Every piece of new knowledge – as well as every new experience – that I can pass on to my children early on in their life will bear fruit one-hundred-fold in the future. Every day, I ask myself the question: have I done everything in my power to do right by them? And then thousands of different thoughts of what we could do, what stories we could read, where else we could go, and what else we might explore keep running through my head. Personally, I think that this is the hardest phase in the human life cycle – although it’s also the one from which you can learn the most. In the nine years since the birth of my first child, I’ve come to understand a lot of things about myself. As a result, I would say that this period marks the beginning of my real life. Children can sometimes understand things better than their parents – other times we must be patient to try and understand their feelings. We must be aware of our individual strengths and weaknesses. This understanding allows you to make the journey from selfishness to humility. You must learn to reconcile your needs and your will with that of the others around you.

And so, I wouldn’t say that it’s been easy to find the right balance between work and home. I often feel like a fireman running between my family and work, putting out fires. And then I also have to be careful not to burn out myself. I’m fortunate that my wife supports my work – especially as I spent a large part of our family’s summer vacation this year working on the illustrations for the new Poetics. And I’m also grateful to my colleagues who help pick up the slack at work when I need to stay home whenever one of my kids gets sick. And yet, all in all, I find that all of these different demands can help make you even stronger – especially when I listen to my elders who have often described this prolonged period of their lives as the most productive one of all.

Through your father Anatoli, you’ve been a part of Tallinn’s Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and its community for your entire life. You’ve been connected to this place – and to what would eventually evolve into the Ukrainian Cultural Center – almost since you were born. What has this place meant to you? How has it helped you become who you are – both as an artist and as a person?

Now this is something on which you could write an entire book. If you spend 28 years of your life building a church as well as the supporting physical and intellectual structure around it, it is bound to make a strong impression. The construction of our church represented a commitment to certain values. While our transitory motives may have been to achieve a kind of personal permanence, the values of the church itself are just as permanent as the walls of this 13th Century building. By constructing the church, I learned about persistence and about the importance of unchanging values.

And yet, it is never possible to stand still. You must either continue to develop or start to slip. There are so many things that need to be done. And the world around you is always changing so quickly. My connection to the Center has given me an idea of what I can change and what I can’t. While the fundamental principles of life should never vary, you must continue to change within this framework in order to keep yourself vibrant and dynamic. I feel that it is the combination of these basic unchanging values coupled with continuous motion – while keeping an open mind – which is critical to becoming an artist. And I learned this truth from my work at the Ukrainian Cultural Center.

Looking back on your artistic journey so far, what advice would you have wanted to give your younger self – that version of you about to step through the doors of the Estonian Academy of Arts on that very first day? And would it be the same advice that you would want share with other potential young artists out there thinking about going to art school?

Even the very idea of making recommendations to your younger self – giving advice on what you should have done differently – is a good one! Why? Because it leads you to ask those all-important questions about what you should be doing with yourself now.

So, here are some of the things that I wish I would have kept in mind twenty years ago:

- If you don’t know exactly what you want to do and who you are, then forget about everything else and figure that out first!

- Set goals for yourself and be laser-focused on achieving them.

- Dare to experience everything connected with what you’ve determined is your purpose in life without the fear of failure.

- If you can’t find what you think you need around you, then go looking for it, figure out how to arrange it for yourself, or just make it yourself. In other words, don’t stand still – figure something out. Be proactive!